Terrorist Tradecraft and the Jihadist Threat to the West

By TorchStone VP, Scott Stewart

Charles Lister’s excellent piece in Foreign Policy notes, “The Biden Administration is dangerously downplaying the global terrorism threat.” I agree with Lister’s premise that it is dangerous to ignore the simmering threat posed by jihadism. As the history of the Islamic State illustrates, it is dangerous to underestimate the ability of jihadist militants to rebound from significant defeats.

While the U.S. and its allies have had some success in killing or capturing key jihadist figures, it is simply far easier to kill an individual than it is to kill an ideology. As long as the virulent and violent ideology of jihadism persists, it will continue to attract new recruits. Jihadist groups therefore will remain a significant threat in areas where there is a vacuum of security and governance including large areas of Africa, the Afghanistan/Pakistan border area, Yemen, and the Levant.

Because of this, I have long held that efforts on the ideological battlefield against jihadism are more critical than the physical one. Efforts on the physical battlefield are obviously needed to keep the military capacity of jihadist militants in check, but only the downfall of their ideology will cause them to be ultimately defeated.

However, factors are serving to mitigate the terrorist threat jihadism poses to the West. The primary factor is the lack of terrorist tradecraft, a void that has been created by the nature and composition of the jihadist movement at this time.

Terrorist Tradecraft

Since the foundation of the modern jihadist movement in the 1980s, hundreds of thousands of militants have received training at jihadist training camps around the world. The vast majority of these militants received training that is similar to that I received during U.S. Army basic training. They received physical fitness training. (As an aside, I love jihadist propaganda videos featuring recruits jumping through flaming hoops!) They are also taught how to use small arms such as rifles, pistols, grenades, and RPGs, and are given some training in hand-to-hand combat and small-unit tactics.

Such training is very useful for recruits being prepared to fight guerrilla warfare in the Sahel or Sulu Archipelago, or hybrid warfare in places like Syria. It prepares militants to fight as a member of a unit within the jihadist group’s military structure. In fact, most jihadist militants across the globe today are engaged in this type of warfare. They may conduct raids and terrorist attacks as part of their irregular or hybrid warfare campaigns, but normally these terrorist attacks are conducted within the group’s primary area of operation and can rely upon the organization’s military command for planning and support.

Basic military training is of limited use to someone being sent to a distant location to conduct a terrorist attack in a hostile environment where they will have to work independently of the jihadist group’s structure and support. The ability to handle a rifle is useful if an armed assault is the chosen type of attack, but the skill set required to successfully operate as an urban terrorist in a hostile environment is more akin to that of an intelligence officer than it is to that of a guerilla fighter. I refer to this set of skills as terrorist tradecraft.

In the intelligence world, tradecraft refers to the techniques and procedures used by an intelligence officer conducting clandestine operations, but the term also implies using these skills with a degree of finesse. Thus, tradecraft is as much an art as it is a science—and like any other art, one can be taught the basics. But it is only through practice that one can become a master of terrorist tradecraft.

This parallel between terrorist and intelligence tradecraft is illustrated by the fact that during the Cold War, Marxist terrorist operatives received extensive tradecraft training from the KGB and the Stasi rather than from the Russian or East German military. Marxist groups such as the Provisional Irish Republican Army and the Abu Nidal Organization made good use of this tradecraft training.

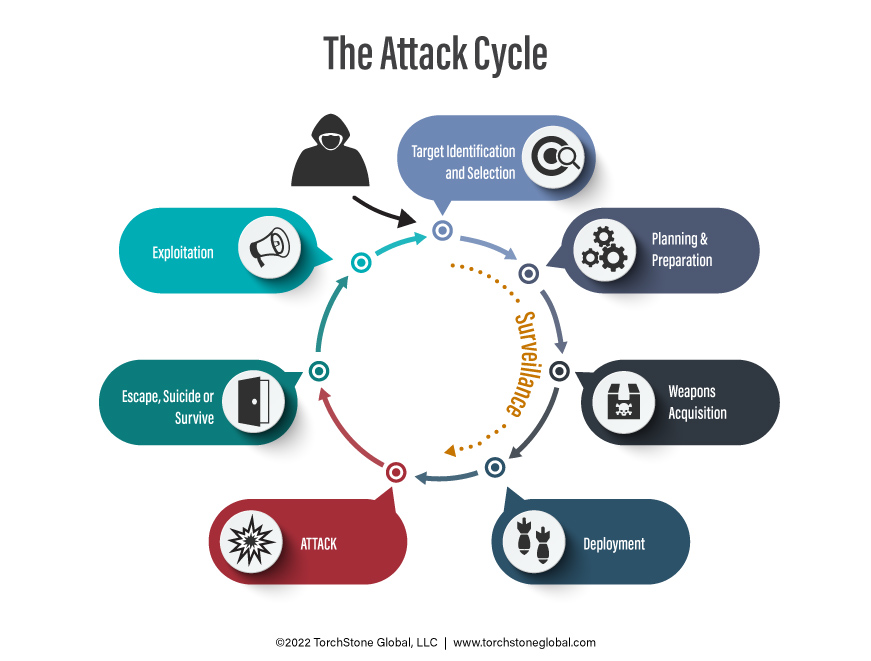

Terrorist tradecraft includes skills such as the ability to travel without detection, clandestine communications, operational security, and covertly transferring money. Once the operatives are established in the location where the attack will be executed, they then need to conduct their attack cycle without being detected. This entails conducting multiple rounds of surveillance on the target, a point in the attack cycle where many plots are thwarted.

Acquiring weapons for an attack can also be a considerable challenge for militants operating in a hostile security environment. Poorly governed combat theaters where jihadist groups normally operate tend to be awash in military ordnance and so it is not difficult to obtain weapons and explosives for an attack. This task is far more challenging in a Western capital where weapons are not easily obtained, and the security forces are actively watching for threats.

Bombmaking is another important element of terrorist tradecraft. Creating a functional improvised explosive device in a war zone where one has ready access to military-grade high explosives, blasting caps and other components is relatively simple compared to making a device where one is forced to fabricate all the bomb components from scratch including the main explosive charge and detonator.

Jihadist operatives like Najibullah Zazi, and failed Times Square bomber Faisal Shahzad illustrate the challenge of building viable explosive devices even after receiving bomb-making instruction in jihadist training camps abroad. This is because the items they were trained to make explosives and bomb components were more difficult to acquire in the West.

A Decline in Tradecraft

Most jihadist militants were only provided basic military training. It was only a very select few who received advanced training in terrorist tradecraft skills. Traveling in the West can be a daunting experience for a Pashtun or Tuareg tribesman raised in a remote area. Because of this, groups such as al Qaeda and the Islamic State have often selected militants who are from Western countries, or who were educated there, for terrorist training to conduct operations in the West.

The CIA, the Pakistani ISI, and other intelligence services provided training to mujahideen militants who fought against the Soviets in Afghanistan during the 1980s. They provided training in bomb-making, attack planning, operational security, surveillance, and other tradecraft skills. Thus, many of the first generation of al Qaeda militants dispatched to conduct attacks such as the 1993 World Trade Center attack, the East Africa Embassy Bombings, the bombing of the USS Cole, and the 9/11 attacks, had received instruction in training camps from instructors who had been trained by intelligence services and were able to pass on that tradecraft to their students.

However, as that first generation of operatives and their trainers was killed or arrested, and as the camps where terrorist training was provided were destroyed, al Qaeda suffered a serious decline in the ability to train new militants in terrorist tradecraft. This has hampered their ability to project their terrorist capability into the West.

The Islamic State experienced a similar dynamic. The first generation of their terrorist operatives, including their founder, Abu Musab al Zarqawi, were trained in camps in Afghanistan. These operatives were later supplemented by members of the Iraqi intelligence service, police, and military who joined them after U.S. forces overthrew Saddam Hussein’s regime. But like al Qaeda, the deaths or arrests of Islamic State operatives and trainers have resulted in a decline in their ability to provide training in tradecraft, and consequently, has limited their ability to project terrorism beyond their core areas of operations.

A Change of Strategy

The drop in al Qaeda’s tradecraft capabilities coincided with an increase in the resources devoted to countering the threat of jihadist terrorism. Because of the difficulty they’ve had in conducting attacks in the West, jihadists began to adopt different strategies.

One strategy adopted by al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) was what I call the “go-long” attack in which planners launched a campaign involving cleverly concealed bombs manufactured at their base in Yemen that were then sent outside of the country to conduct attacks. One of these attacks involved an assassination attempt against the Saudi counterterrorism chief Prince Muhammad bin Nayif. Other attacks in this campaign involved an attempt to detonate an underwear bomb in an aircraft flying over Detroit, and bombs concealed inside computer printers sent via air cargo. AQAP’s go-long campaign was disrupted by the death of the ideologue promoting the campaign, Anwar al Awlaki, as well as the death of their master bombmaker, Ibrahim al Asiri.

Al-Shabaab attempted a similar attack against a Turkish airliner in 2016 using a bomb concealed in a laptop computer, but it has been several years since we have seen such an attack.

The second strategy was the jihadist embrace of leaderless resistance. Jihadist military theoretician Abu Musab al-Suri first began promoting the concept in 2004, when he combined leaderless resistance theory with the individual responsibility for conducting jihad. The leaders of AQAP eventually picked up the idea in 2009, penning an article in the group’s Arabic language magazine, Sada al-Malahim, in which they encouraged Muslims living in the West to operate on their own instead of attempting to travel overseas to receive training with jihadist groups. Individuals were encouraged to conduct simple attacks against soft targets using readily available weapons such as firearms and edged weapons.

The viability of this concept was demonstrated in November of 2009 when a member of the U.S. military who had been radicalized by AQAP conducted a simple attack against an army processing center at Ft. Hood with a handgun. The success of the attack motivated AQAP to dramatically increase its efforts to inspire and equip other jihadists in the West to emulate the grassroots attack, even launching an English-language magazine called Inspire.

These events caused al Qaeda’s core leadership to embrace leaderless resistance, and they published a video in 2011 in which American-born spokesman Adam Gadahn encouraged Muslims living in the West to conduct attacks against soft targets near where they live, using whatever weapons they could get their hands on.

Following their split from al Qaeda in 2013, the Islamic State also began advocating leaderless resistance. A September 2014 message from Islamic State spokesman Abu Muhammed al-Adnani reiterated AQAP’s earlier call for jihadists living in the West to conduct attacks against soft targets, no matter how basic.

While there have been occasional attacks by operatives dispatched from the core jihadist groups, such as the November 2015 Paris attacks, the primary jihadist terrorist threat to the West today stems from grassroots jihadists living in the West who are radicalized and operationalized by the jihadist movement’s leaderless resistance efforts.

Possibility of Improvement?

While jihadist militants are still quite active in many parts of the world, the primary military threat they pose is that of insurgent or hybrid warfare. They also pose a significant terrorist threat within their primary areas of operation. It is certainly possible for jihadist groups to begin to improve their grasp of terrorist tradecraft once again, but such tradecraft improvements will become visible as terrorist attacks conducted in their primary areas of operation demonstrate an increasing degree of skill and sophistication.

Jihadist groups are also likely to demonstrate growing reach by projecting their terrorist capabilities in attacks against targets on the periphery of their primary areas of operation before launching more ambitious transnational attacks. A good example of this was AQAP’s proof of concept attack against Prince Muhammad bin Nayif in Saudi Arabia before attempting to attack aircraft flying over the United States. In other words, there are likely to be substantial warning signs before any group gains the capability to directly attack the U.S. homeland.

Therefore, will be important to continue to monitor the terrorist attacks of jihadist militant groups for signs of improved tradecraft capabilities and range.