Extremist Influencers’ Role in the Social Media Threat Continuum

By TorchStone VP, Scott Stewart

During the week of February 5, I attended the Association of Threat Assessment Professionals (ATAP) Winter Meeting. While I was attending the conference primarily to share my ideas on why the concept of the Attack Cycle is still relevant today with my friend and former Diplomatic Security Service colleague Dave Benson, I was also there to learn from others. ATAP conferences are packed with excellent speakers discussing interesting topics. I attended presentations on subjects such as the online behaviors of targeted attackers, the copycat effect among incels, neo-Nazis, and school shooters, and several interesting case studies examining attacks and thwarted attacks focused on the pre-attack indicators and behaviors of the subjects.

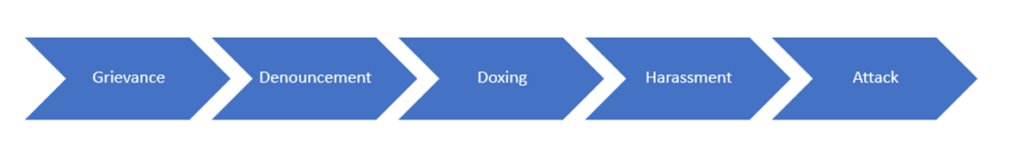

In many of these presentations, I repeatedly noted connections between the cases being examined and the concept of the social media threat continuum. It occurred to me that it would be good to elaborate on the continuum and examine the role of “extremist influencers” in the social media threat continuum.

What is an “Extremist Influencer”

Extremist influencer is a term I’ve adopted to refer to ideologues who use social media to promote violent extremism. While mainstream social media influencers use their fame and platforms to hawk things like cryptocurrencies, lip plumpers, and Stanley drinking cups, extremist influencers use their profiles to promote violent ideologies.

I’ve written for many years about the leaderless resistance model of terrorism, which has been adopted by violent extremists of all stripes, including white supremacists, jihadists, and anarchists. As the concept of leaderless resistance was taking flight in the 1980s and early 1990s ideologues used pamphlets, video and audio tapes, radio programs, public access television, and internet relay chat rooms to spread their message. Their reach expanded considerably in the internet age, and it is no mistake that violent extremists were early adopters of the internet with websites like Stormfront and Azzam.com quickly drawing thousands of regular visitors.

However, the combination of smartphones, and social media apps supercharged the efforts of extremist ideologues practicing leaderless resistance to reach new audiences with their vitriolic messages and provide them with a truly global reach. This reach was demonstrated by the way beheadings videos from Iraq encouraged followers to conduct beheadings and other attacks in Europe, and how the xenophobic manifesto of an attacker in Norway could inspire radicalized individuals to conduct armed assaults against mosques in New Zealand and a Walmart in El Paso.

This reach, when combined with new approaches to propaganda that included sometimes gory videos of bombings, beheadings, and armed assaults quickly drew the attention of millions of morbidly curious people and helped draw in those who were ripe for radicalization. Using video cameras to livestream attacks served to further “gamify” acts of terrorism and encouraged both contagion and copycat attacks among radicalized individuals and small groups. This gamification is reflected by the statements of attackers who have noted that they sought to achieve the “top score” via their attacks.

Extremist influencers also sought to equip those they radicalized with the skills required to conduct attacks by publishing how-to guides like Inspire Magazine or posting videos containing step-by-step instructions for making bombs and other operational acts.

The communities created by extremist influencers also served to provide isolated radicals with a sense of community and belonging that the influencers were then able to translate into a sense of duty that served to mobilize isolated radicals into operationalizing their radical beliefs and carrying out real-world attacks. Thus, these isolated radicals were motivated to truly “think globally and act locally.”

These communities often venerate members of their community who decide to conduct attacks by posting their martyrdom videos, attack videos, and manifestos. This lionization is not just something seen in jihadist networks. In white supremacist communities, these attackers are referred to as “saints.”

The influence exerted by these ideologues on the networks they create can also continue long after they are arrested or killed. For example, American-born al Qaeda ideologue Anwar al Awlaki’s videos continued to be circulated widely after his death in Sept. of 2011 and inspired attackers such as the one who killed 49 people during an armed assault at the Pulse Nightclub in Orlando, FL in June of 2016. It wasn’t until 2017 that YouTube removed some 70,000 videos featuring his sermons, but al Awlaki’s videos continue to be widely circulated in jihadist circles today.

Role of the Extremist Influencer

It may be instructive to examine the extremist influencers’ role in the context of the social media threat continuum’s various segments.

Grievance

The social media threat continuum for any ideology always begins with a grievance. In expressing the grievance, the extremist influencer will seek to articulate the grievance and describe how it impacts the “in-group” or the universe of people the idealogue is attempting to reach and radicalize. The influencer will also identify the out-group(s) who are the purported source of the actions against the in-group that have resulted in the grievance(s), and then call for violence in response to the grievance.

Public Denouncement

The denouncement phase of the social media threat continuum is where extremist influencers identify and denounce specific out-group individuals or entities that are considered to be enemies of the in-group. Influencers living in ungoverned spaces like Syria or Afghanistan have more freedom to call for the deaths of denounced targets than influencers living in the West, where they are under close law enforcement scrutiny.

Doxing

Depending on the nature and location of the extremist influencer, they may or may not be involved in doxing individuals and entities identified as enemies of the in-group. Doxing refers to the tactic of releasing sensitive or private information about an implied target with the intent of intimidating the target or facilitating others to conduct a physical attack. The Islamic State social media accounts have published several “kill lists” that released personal information pertaining to enemies in Europe and North America. Again, those influencers living in places where they are under close law enforcement scrutiny tend to be more discreet in doxing targets they have denounced for fear of arrest.

Harassment

While not all extremist movements encourage followers to harass enemies of the in-group rather than attack them, some do, including climate extremists, anarchists, and even certain elements of the white supremacist movement such as the Patriot Front. Some influencers publish instructions or even how-to guides for planning harassment actions, offer legal advice for those participating in them, and often support them if they are caught and arrested.

Attack

Many extremist influencers publish step-by-step guides to help radicalized adherents conduct attacks. Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula’s Inspire Magazine is perhaps the best known of these. The bomb-making instructions contained in the magazine were used to conduct several attacks including the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing. Other examples are the Earth Liberation Front’s Timed Incendiary Device Manual and the Animal Liberation Front’s Arson-Around with Auntie ALF. Influencers will often publicize attacks conducted by their adherents and laud the attackers. Sometimes they will also critique attacks and provide tips on how the operation could have been conducted more effectively as learning points for future attackers.

Not all extremist influencers conduct attacks themselves. Some achieve their fame and status through other means, like Osama bin Laden, who constructed terrorist training camps and enabled many others to conduct attacks. A forthcoming installment in this series will examine the attributes that make an effective extremist influencer.

However, as demonstrated by several cases, attacks tend to generate a great deal of publicity and this can result in an attacker becoming an influencer, whether they escape like Eric Rudolph, are arrested like the Norway and Christchurch attackers, or die.

As new social media apps and technologies are developed, extremist influencers and their followers continue to adapt their approaches to disseminating propaganda. This means that investigators, analysts, and others seeking to prevent attacks will have to continue to evolve their techniques to monitor and understand trends that emerge along the social media threat continuum.

This is the second part in an occasional series on the Social Media Threat Continuum. Part one discusses how the combination of leaderless resistance and social media is impacting the current threat environment.