The Social Media Threat Continuum

By TorchStone VP, Scott Stewart

During my career, I have found analytical frameworks very useful for understanding and assessing threats.

While all frameworks are imperfect to some extent—face it, no model can ever fully represent every possible sequence of events in the real world—nonetheless, frameworks are helpful for those seeking to understand threats and place them into context.

Some examples of frameworks I often refer to when I am assessing threats are the attack cycle and the pathway to violence.

Over the past several years, I’ve been tasked to conduct assessments of the threat posed to individuals, companies, and organizations by extremist organizations or movements that are operating under the principles of leaderless resistance, and that are using various social media applications as their main communication channel.

I thought I’d share a model I’ve developed to help understand the range of threats posed by such actors. But first, I’d like to discuss how the combination of leaderless resistance and social media is impacting the current threat environment.

Leaderless Resistance and Social Media

While the practice of leaderless resistance is actually quite old, perhaps one of the clearest modern descriptions of the operational model was penned in 1983 by Louis Beam and published in a Ku Klux Klan newsletter.

In Beam’s conceptualization of leaderless resistance, the violent extremist movement should be divided into two tiers.

The first element is the legal and above-ground “organs of information,” who would “distribute information using newspapers, leaflets, computers, etc.”

The ideologues who comprised the organs of information were encouraged to use the protection of First Amendment free speech to shield their operations and were advised to not conduct any illegal acts.

Instead, their role was to articulate grievances, provide direction for those conducting attacks, identify enemies of the movement, and issue propaganda for recruitment purposes.

The second tier of the extremist movement would be made up of individual operators and small “phantom” cells that would conduct attacks and other illegal activities.

These people were to remain low-key and anonymous, with no connections to, or communications with, the above-ground activists. In today’s parlance, we often refer to this violent, operational tier of the extremist movement as “self-initiated terrorists” or “grassroots terrorists.”

This strict separation between the segments of the ideological movement is meant to prevent government agencies from being able to prosecute the ideologues for the crimes they encourage.

It is also intended to make it more difficult for the government to identify individual actors and infiltrate or compromise the small cells.

When Beam penned his description of the leaderless resistance model, the main channels of communication extremists were using were somewhat limited in reach and consisted primarily of underground newspapers, pamphlets, a few shortwave and pirate radio stations, and in some cases cable TV public access channels.

By the time Beam’s essay was reprinted in 1992, extremists had begun to adopt internet relay chat channels, computer bulletin board services, and email lists to transmit propaganda.

By the mid-1990s extremists of all stripes had adopted the internet and websites for jihadists, white supremacists, and anarchists rapidly propagated in cyberspace.

Fast-forward to today and social media has become a huge game changer in terms of propagating extremist material.

The internet has supplanted print and broadcast media in reach; and social media applications have become important, if not the primary, source of news and other information for most people.

Social media applications have democratized the media and have allowed extremists and extremist movements to become their own media—even to the point where they can live broadcast terrorist attacks.

In many cases social media applications are also encrypted, thus further complicating the efforts of law enforcement and security agencies to monitor their communications.

As has been widely reported by a variety of academic organizations, social media algorithms allow people to rapidly become inundated by extremist material.

Extremist ideologues who are essentially “ideological social media influencers” can reach a wide audience of like-minded individuals.

While mainstream social media influencers use their celebrity to hawk yoga pants and mascara, their extremist counterparts use their platforms to recruit, radicalize, and operationalize grassroots militants to conduct attacks.

The Islamic State was perhaps the most successful extremist movement to use social media to spread its influence and message and has effectively employed social media as a tool for both its hierarchical operations in its main areas of influence as well as in its leaderless resistance operations in more hostile environments.

However, the combination of leaderless resistance and social media has been adopted far beyond the jihadist and white supremacist movements, and it is also being used by anarchists, and single-issue extremists including incels, animal rights extremists, environmentalist extremists, anti-abortion extremists, etc.

The wide array of movements employing social media-fueled leaderless resistance has created a need to develop a framework that can help understand and contextualize the threats emanating from them.

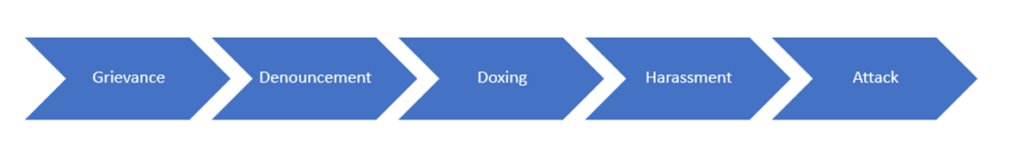

Here’s how I think of these threats along a continuum from least to most dangerous.

Social Media Threat Continuum

Grievance

Extremism is always fueled by some sort of grievance.

For example, recently we have seen denouncement, harassment, doxing and physical attacks linked to grievances over a variety of issues including the so-called “great replacement,” the inability of some men to have a physical relationship with women, and vaccine mandates.

These grievances can be either real or imagined. Just because a grievance appears delusional or fantastical to an outside observer doesn’t mean that it is not very real to the person holding it.

The grievance is not really a threat but rather serves as a starting point for the continuum.

Since the threats on the continuum flow from the grievance, it is important for protective intelligence teams to identify and monitor grievances.

Public Denouncement

Denouncement involves publicly ridiculing or criticizing a target in order to classify them as an enemy of the ideology/organization and its supporters.

Denouncement is a form of intimidation and can generate a great deal of fear in the target.

Denouncement is most harmful when it is done by an extremist influencer with a significant following and who wields significant ideological authority within the movement.

The social media account of a high-profile extremist influencer with 100,000 followers will obviously have a much broader reach and impact than one with only a handful of followers.

The denouncements of someone widely recognized to have ideological gravitas within the movement also bear more weight on impressionable followers than an unknown figure.

Doxing

Doxing is the practice of releasing private information about a target on the internet with malicious intent.

It is often done to encourage others to harass or attack the target.

While doxing by itself does not cause physical harm, it can provide critical personal information to those wanting to do harm to the targets of the doxing—information that can be used to commence physical surveillance of the target.

Doxing is also used as a form of intimidation and can cause intense feelings of fear, as well as psychological stress and pressure on the target.

This fear and pressure will often increase dramatically if the target receives threats or harassment at their home, or via their phones—or if they receive threats directed against their family.

Often the subject of the doxing is overwhelmed by the personal information contained in the dox which creates a sense of “information shock,” the unfounded fear that the person doing the doxing knows everything about the target and has even been conducting extensive physical surveillance on them.

Harassment

Harassment can take many forms including online trolling, “swatting” calls (whereby a call is made to 911 reporting a serious crime in the hopes that a Swat team will be deployed), and even things such as sending items such as pizzas or pornography to a target’s home.

Harassment can also involve vandalism, leaving stickers or flyers near a target’s home or office, or even protesting at or near the target’s residence.

Harassment can be unsettling, and psychologically impactful, especially when harassment activities occur near the target’s home and family.

Harassment is quite often preceded by denouncement, doxing, and online harassment before it escalates to more serious forms.

This is a pattern we have seen repeated, especially when a movement group or leader wants to avoid being directly tied to the activity.

The group or the leader or another ideological influencer will publicly denounce a target on social media, the target is then doxed—sometimes by an “anonymous” source, and then group members or supporters harass the target on social media.

Physical attack

A physical attack intended to injure, or kill is obviously the direst threat.

Attacks can either be targeted against a specific person, e.g., a plot to kill a Supreme Court Justice or kidnap a governor, or against a general target, e.g., a crowd at a supermarket or on the street.

One of the historical weaknesses of lone attackers and small cells has been the lack of the terrorist tradecraft necessary to conduct a successful attack without being detected.

Indeed, this lack of tradecraft has often resulted in botched attacks or has led would-be attackers to reach out for help with their plans which has resulted in them becoming ensnared in law enforcement sting operations.

While it is generally not difficult to murder someone, the complexity increases in the case of a targeted killing of someone who the attacker is not intimately familiar with.

The task becomes even more difficult if the attacker wants to escape without being caught.

Contextualization

While I have listed the continuum in terms of severity, threats do not always follow a linear progression along the continuum.

For example, an actor can jump right from a grievance to harassment or a physical attack, and conversely, not every grievance leads to doxing, much less harassment or a physical attack.

Also, unlike the pathway to violence model whereby a single actor progresses through the stages, in the social media threat continuum, different elements of the movement will often execute different stages of the continuum.

For example, an extremist influencer can denounce a target, while a “cyber commando” doxes the target and a self-initiating extremist begins to plan an act of harassment or attack.

In some cases, the steps may also be taken concurrently, or even out of order, with a doxing occurring after someone has already decided to begin planning an attack or harassment.

Because of this, the continuum is best thought of as an elastic guide to help place threats and actions into context, rather than a rigid framework.