The Importance of Understanding the Attack Cycle

By TorchStone VP, Scott Stewart

In the piece I wrote on the need for, and functions of protective intelligence programs, I discussed how one of the foundational precepts in the way TorchStone approaches protective intelligence is by recognizing the reality that intentional attacks “don’t just happen.” They are the result of a discernable process that can be detected — and interrupted. This process is called the attack cycle. Some people refer to it as the “terrorist attack cycle” but I would argue that the same steps are also used by other violent actors as they plan an attack, regardless of their motivation. An unbalanced stalker, workplace attacker, school shooter or violent criminal will follow the same planning process, so I prefer to simply refer to it as the attack cycle.

The attack cycle is an important concept because it provides a useful reference for investigating or analyzing past attacks. However, I believe its most important function is to provide a framework protective intelligence practitioners can use to understand, identify and detect behaviors associated with an imminent attack to prevent the attack from being launched. Once an attack is initiated, it is impossible to put the bullets back into a firearm or to turn back the blast wave and shrapnel of a bomb. It is always better to avoid or prevent an attack than it is to react to one. Looking for attack cycle behaviors is an important proactive tool in the protective intelligence kit.

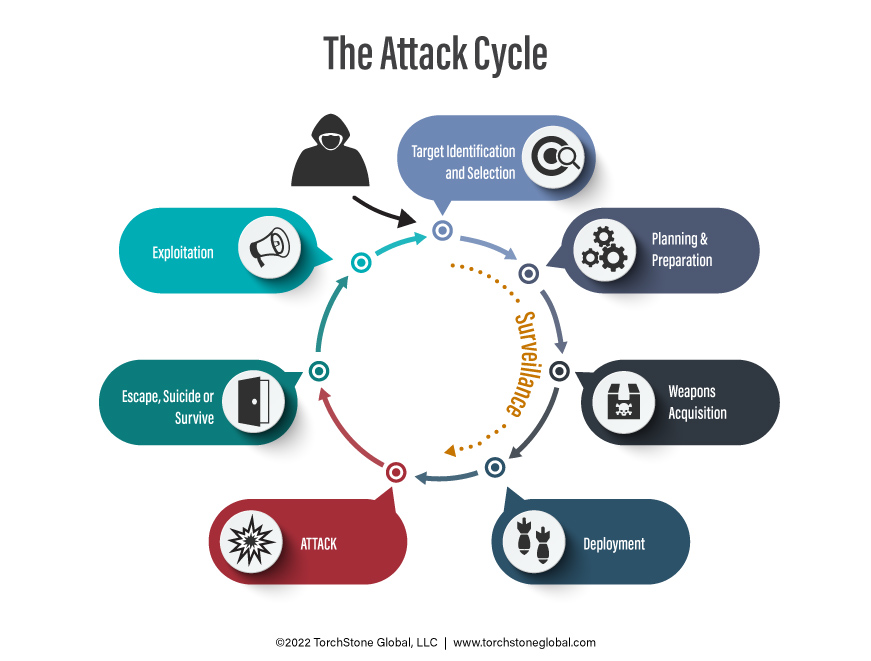

There are several variations of attack cycle models that tend to highlight different aspects of the cycle. Some insert multiple surveillance phases into the cycle or a final target selection phase, while others add a separate rehearsal or dry run phase. There is nothing wrong with those models and they all have merit; however, but for the purposes of our discussion, the graphic below depicts my conceptualization of the attack cycle.

When it comes to applying the attack cycle, one of the mistakes I frequently see people make is attempting to apply it too rigidly to a specific attack. When the attack cycle is applied in this type of inflexible manner, there is a tendency to jump to the conclusion that the model does not work and then abandon it. To avoid this trap, it is important to think of the attack cycle as an elastic and general guideline for helping us understand the steps required to plan and execute an attack, as well as a helpful guide to help contextualize pre-attack behaviors.

As we begin to apply the concept of the attack cycle to actual plots and attacks, it becomes readily apparent that there can be a great deal of variation in how the attack cycle is completed depending on the particular actor or actors involved, as well as their level of training, skill and tradecraft. For example, a complex terrorist organization with professional planners and dedicated surveillance and logistics cells will progress through the attack cycle in a different manner than will a lone assailant. However, despite these differences in how they accomplish the activities associated with the attack cycle, they will all nevertheless be bound to follow these general steps when conducting an attack.

In the following sections I will examine each step of the cycle. By using examples from past attacks, plots and sting operations, I will illustrate how different types of assailants are bound by the attack cycle. I will not discuss the attack or execution phase of the cycle since that is self-evident.

Target Identification and Selection

This is the step in the attack cycle when the type of target to be attacked is identified and a specific target to be attacked is then selected from a list of potential targets. For example, in 2017, the Islamic State Wilayat Sinai decided they wanted to attack a Coptic church to stoke sectarian tensions in Egypt. They then specifically selected the Church of Saint Menas in Cairo as the target for their Dec. 29 suicide bombing.

By definition, intentional attacks must involve pre-selected targets. Because of this, it is not difficult to see how this phase of the attack cycle applies to all types of attackers. Now, that being said, there is a great deal of variation in how target identification and selection is accomplished depending on the type of actor involved. In the case of a sophisticated terrorist organization with highly trained cadres, they may search extensively across a country or even region to identify a suitable target once the group’s leadership has selected the type of target they would like to attack. For example, when the leaders of Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb decided to attack hotels housing westerners in West Africa, it took them months of research and surveillance to identify their two targets; the Splendid Hotel in Ouagadougou, attacked in Jan. 2016, and the Étoile du Sud hotel in Grand-Bassam, Ivory Coast, attacked in March 2016. The two hotels were located some 700 miles apart.

On the other end of the spectrum, lone assailants or small cells operating under the leaderless resistance model of terrorism tend to hit targets they are more familiar with and that are closer to home. For example, the accused shooter in the Oct. 2018 attack on the Tree of Life synagogue lived only some 10 miles from his target.

In the case of a stalker, target selection is the result of a fixation the attacker has with the target, and oftentimes this fixation develops long before the would-be-attacker develops a specific grievance or even begins to think about conducting an act of violence against the target.

In workplace violence cases, attackers often select specific people or groups of people they have a grievance against as their targets. In some cases, the shooters will even spare employees they do not have a grievance against. The killer in the June 2019 shooting at the municipal building in Virginia Beach refrained from shooting several people he encountered during his rampage.

The targeting of people or groups of people the attacker has a grievance against also happens in most school shootings. The school itself and the students and faculty inside it are also sometimes selected as targets rather than specific people. This was the case in the Dec. 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School.

Surveillance

As I noted above, some attack cycle models delineate specific surveillance phases. However, surveillance can and does occur throughout a large portion of the attack cycle from target selection and identification through the execution of the attack. I believe indicating that surveillance only occurs during certain phases of the cycle can be misleading and possibly harmful.

The amount of surveillance required to select a target, plan an attack and launch the attack can depend considerably on the type of attacker, the type of attack and the target itself. In some cases, the surveillance can take weeks or even months. David Headley, who conducted the pre-operational surveillance for the Nov. 2008 Mumbai attacks, reportedly made five trips to Mumbai in 2007 and 2008 to gather the information needed to select the targets and plan the assault. In a more recent case, members of the white supremacist group The Base made several trips to surveil the Bartow, Georgia home of a couple associated with the Antifa movement they were planning to assassinate. Kidnappers, bank robbers and other violent criminals also often conduct extensive surveillance of potential targets in the process of selecting one.

The amount of research and surveillance required during the attack cycle will also be different for an internal attacker as opposed to an external actor. Insiders have intimate knowledge of the layout of a targeted facility, as well as the security programs, policies and procedures in place. They also have natural cover for status and action as they conduct any additional surveillance required, giving them a distinct advantage over an outside attacker.

Criminals, terrorists and other attackers often have very little in the way of surveillance training and tend to exhibit poor surveillance tradecraft and demeanor. This makes most attackers vulnerable to detection while conducting surveillance — but only if someone is looking for them.

In addition to conducting physical surveillance of potential targets during the target selection and planning phases, attackers will often also conduct Internet research. This research can be as basic as compiling a list of potential targets in a city, or as detailed as obtaining building blueprints or combing through the social media of employees at the targeted facility to find photos of building access passes in order to make a counterfeit.

Planning and Preparation

The planning and preparation phase of the attack cycle can also vary considerably depending on the actor involved and the type of attack being planned. Again, however, it is simply not possible to have an intentional attack without at least some degree of pre-attack planning and preparation. This phase not only includes developing the attack plan, but also a number of preparatory steps such as acquiring weapons and other materials required for the attack, training, rehearsals or dry runs, etc. This stage can also include additional surveillance if that is required to establish the pattern of the target for an assassination or kidnapping, or to answer specific questions the planner may have about security measures at the target. For example, the number of guards, their deterrent capability, types of locks on doors, CCTV coverage and the like.

In some past attacks, the planning and preparation stage has been quite elaborate. Consider 9/11 where some of the attackers were sent to the U.S. many months in advance to attend pilot training and the elaborate dry-runs the attackers made that included taking the exact same flights from the same airports and sitting in first class so they could better observe cabin crew procedures. The 9/11 Commission Report provides a detailed account of this planning process.

Perhaps one of the most detailed accounts of the planning and preparation phase for a terrorist attack was the document compiled by the attacker who conducted the July 2011 vehicle bombing and armed assault in Norway. The attacker provided a meticulous account of how he prepared himself physically (using anabolic steroids) as well as psychologically to kill other people. He also discussed exactly how he acquired his firearms, as well as the precursor chemicals he needed to make the vehicle bomb. He even noted what brands of blenders worked the best for grinding the ammonium nitrate prills used to make the improvised explosive mixture, presumably to help future attackers.

Of course, not every attack will take months or years to plan and prepare for. At the other end of the spectrum, a lone attacker who decides to conduct a Molotov cocktail attack against a particular building may be able to plan such an attack in only a few hours and obtain the materials he needs to construct the incendiary device in his own garage.

Deployment

Deployment means getting the attacker or attack team and their weapons the attack site so the attack can be conducted. For some attacks, this can be a very complex process, like when some 40-50 heavily armed Chechen militants seized the Dubrovka Theater in Moscow in Oct. 2002. Deployment for this attack not only involved transporting a large group of armed militants to Moscow from Chechnya along with their small arms, but the attackers also brought in large quantities of explosives that they proceeded to deploy throughout the theater to deter Russian security forces from storming the premises.

In the case of the April 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, deployment simply meant the brothers driving to the area near the finish line with the pressure cooker bombs they had made and then placing the backpacks containing the devices amid the crowd.

In the case of the unstable stalker who attacked twenty-year-old Japanese pop music star Mayu Tomita, deployment consisted of taking the subway to the venue where she was scheduled to perform with the kitchen knife he used to stab her.

Escape, Suicide or Survive

Some have argued that the escape step in the attack cycle is no longer relevant in the post-9/11 world, but I disagree. Even in cases where a suicide attack is conducted, often those who dispatched the suicide attackers, or in the case of leaderless resistance, radicalized and operationalized the lone attacker, do themselves seek to escape. In Nigeria, Abubakar Shekau and his lieutenants dispatched hundreds of suicide bombers, many of whom were young girls. Yet despite this, Shekau and his staff have not been eager to become “martyrs” themselves. Even among lone attackers inspired by the Islamic State, not all of them are willing to become martyrs. Witness the San Bernardino shooters attempt to flee after conducting their Dec. 2015 armed assault

Many homegrown violent extremists, school and workplace shooters do, however, commit suicide after their attacks. The Las Vegas mass shooter, the Virginia Beach shooter, and the Sandy Hook attacker are all examples. The Pulse nightclub attacker stayed at the scene and shot it out with responding police before being shot dead.

Not all attackers, however, are suicidal. Rather than confront responding police, the shooter in the Stoneman Douglas High school shooting abandoned his guns and left the school among a crowd of students running from the building. Other attackers such as the shooter at the Capital Gazette in Annapolis in June 2018 or the Norway attacker simply surrender without a struggle when confronted by police. For these attackers this step became about survival. The Norway attacker specifically sought to survive so that he could then better exploit his attack.

Exploitation

In the case of a kidnapping or a bank robbery, the exploitation is more about spending the ill-gotten proceeds of the violent crime. But in cases of armed assaults, assassinations or bombings, it is more about promoting the attack as “propaganda of the deed.” In the case of the unstable gunman who attempted to assassinate President Ronald Reagan, he had hoped to gain the attention of an actress he had an irrational fixation on.

In the early days of terrorism, the exploitation phase depended on media exposure and it is no mistake that the rise of terrorism paralleled the development of mass distribution newspapers, and telegraphs to transmit news nationally and internationally. More recently, the Internet, and social media in particular, has provided attackers the opportunity to become their own media, and we have even seen jihadist attackers in France and white supremacists in New Zealand and the United State livestream their attacks.

Even in cases where the attacker commits suicide or is killed by police, they often leave written or video statements they intend to be used to promote the cause that motivated them to conduct their attacks. Al Qaeda and the Islamic State have used these videos and photos to claim credit for the attack by inspired individuals in the West. In online forums frequented by misogynistic Incels or white supremacists, these statements help the attackers become celebrities to be emulated. And speaking of emulation an entire sub-culture of “Columbiners” or fans of the Columbine High School attackers have emerged, and a number of school shooters have been motivated or influenced by this community.

Even when an attacker doesn’t seek to actively exploit the attack themselves, they can still become criminal celebrities who can be idolized by other troubled souls. For example, the man who stalked and murdered actress Rebecca Schaeffer in July of 1989, sat down after shooting her and began reading Catcher in the Rye, a clear nod to the man who did the same thing after assassinating John Lennon in Dec. 1980.