Four Workplace Violence Myths

By TorchStone VP, Scott Stewart

Recent workplace shootings in Indianapolis, IN, Orange, CA, and Bryan, TX, serve to highlight the persistent and pernicious problem of workplace violence in the United States.

Last week, my colleagues Malique Carr and Howard Snyder discussed how the return to work after the COVID-19 pandemic will pose unique challenges on workplace security—specifically in terms of workplace violence.

Unfortunately, there are many false narratives that serve to hamper people’s ability to understand, and more importantly prevent or mitigate, the threat posed by workplace violence. I examine four of those myths here.

1. “It Happens All the Time”

Despite the heavy media coverage that workplace violence incidents attract, workplace violence is not as widespread as many people believe.

In 2019, the most recent year statistics are available, there were 5,333 workplace deaths in the U.S. Of these deaths, 761 were due to intentional injury by a person, and of those 761 fatalities, 363 were killed in shootings and 42 in stabbings. This compares to 2,122 transportation-related deaths, and 880 deaths from falls, trips, or slips.

To place this into a larger context, there were 19,141 homicides in the U.S. in 2019; this means that the 761 workplace “deaths by intentional injury” were equal to less than 4% of the overall homicides in the country.

When we calculate these 761 deaths as a murder rate per 100,000 of the 125-million-person U.S. workforce, we get a murder rate of .60. This is much lower than the murder rate in the general population in the United States, which was roughly 5.0 in 2019.

Of course, not all workplace violence incidents end in death. In fact, far more people are injured in workplace violence incidents than are killed. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 20,790 workers in the private industry experienced trauma from nonfatal workplace violence in 2018.

To place this number in context, consider that there were some 2.8 million nonfatal workplace injuries and illnesses in 2018. In other words, out of the total, only 0.74% of injuries were related to workplace violence.

When we calculate these non-fatal injuries from workplace violence as a crime rate per 100,000 workers, we get a rate of 16.63. This compares to the general violent crime rate of 366.7 per 100,000 for the population of the United States in 2019.

So, while workplace violence is a significant and deadly problem—one that can have a dramatic impact on the people and companies victimized by it—the numbers demonstrate that it is not nearly as widespread as many people believe.

This misperception is due to the heavy focus such incidents receive in the news media. Workplace violence is something to be concerned about, and efforts certainly must be made to prevent it, but it is not a cause for panic.

2. “He Just Snapped”

Contrary to popular belief, workers rarely “just snap” and start shooting their managers and colleagues suddenly and without warning.

Most instances of workplace violence are the result of a collection of factors and grievances that accumulate over time.

Failing relationships, financial problems, a lack of job advancement, and real or perceived injustice at the hands of a co-worker or superior have all contributed to past outbreaks of violence in the workplace.

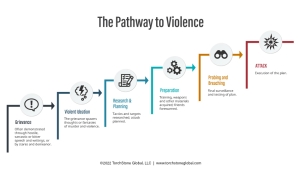

Most significantly, the process through which an aggrieved worker progresses as he moves from a grievance to an attack, known as the “pathway to violence,” is observable.

This means there are almost always indications that a potential attacker is progressing along the pathway.

These indicators provide opportunities to disrupt the cycle before an attack can be launched.

Such interdiction can also be used to get professional help for an employee who is struggling with mental health or other issues.

Progression along the pathway to violence is not automatic. Most people who harbor grievances do not go on to conduct an attack.

Furthermore, it is not a continuous process or even a one-way path. Many people will stay at one level and never progress to the next and others will turn back at some point before conducting an attack.

As we see through the pathway to violence, most workplace violence attacks are pre-planned, which also means that the attacker must progress through the attack cycle—and are vulnerable to detection as they do so.

This leads us directly to the third myth.

3. “There’s Nothing We Could Have Done to Prevent It”

To the contrary, after nearly every significant incidence of workplace violence (or other mass shootings for that matter), it does not take long before reports emerge of warning signs that were either ignored or not reported.

Sometimes these warning signs can include overt or veiled threats, but not every attacker makes threats—sometimes the indicators are more subtle.

Because of this, it is important for everyone in a company to receive training in spotting the signs that a person may be progressing along the pathway to violence or passing along the attack cycle.

Such training must not only contain examples of what to report, but also clear instructions on who the report should be made to and how.

Early reporting of individuals who may be showing indicators they are contemplating violence allows security departments to get on the proactive side of the action/reaction equation.

Rather than responding to an attack in progress, training employees to report behavior that could indicate a potential problem allows security to coordinate with people managers, human resources, mental health professionals, and law enforcement to investigate potential problems.

This then permits them to identify potential perpetrators of workplace violence before they can strike.

4. “Countering Workplace Violence is the Security Department’s Responsibility”

Nothing can be further from the truth.

Countering workplace violence is everyone’s responsibility.

Even in companies with world-class corporate security departments with protective intelligence teams, a company’s employees are the first line of defense against workplace violence.

Co-workers and first-line managers have far more and far closer contact with most employees than the security team does. This places them in an ideal place to observe and report troubling behaviors.

These close personal interactions can often identify red flags such as grievances a person may harbor, the violence he is fantasizing about, his newly acquired fixation with guns, or elements of leakage.

No matter how many CCTV cameras and other equipment the security team has, they will never be able to read the mind of a troubled employee.

Security teams, therefore, depend on employees to alert them to potential problems. When the employees take responsibility for their own and the company’s security, they can form a robust network of tripwires to help identify and stop a possible attacker.

Communication

Of course, security teams must also handle such tips in a discreet and professional manner. If they lose the trust and confidence of the workforce, it can be very difficult to win it back.

This brings up the importance of communication. Training and communication from management and the security team are as important as communication from the employees to report threats.

Managers and human resources personnel must inform employees and access control officers when a co-worker has been terminated and is no longer permitted in the workplace. If a former employee issues a threat, the management and security team must communicate that danger to the rest of the staff so they can be vigilant, rather than trying to ignore or hide the threat.

Honest and transparent communications go a long way in winning and maintaining the trust of the employees and this trust is critical because employees play such an important element in protecting all organizations from workplace violence.

While workplace violence is a low-frequency event, it has a high impact. Because of this, everyone from the C suite down to the rank-and-file workers must work together to spot and report the indicators that can help prevent attacks.