Protective Intelligence Case Study: The D.C. Mansion Murders

By TorchStone VP, Scott Stewart

On the afternoon of May 14, 2015, the Washington, D.C., Fire Department was called to respond to a fire at a large brick home in the city’s upscale Woodley Park neighborhood. As firefighters battled the flames, they discovered the bodies of three adults and a child inside the home. However, as firefighters pulled the bodies out, they discovered the victims had not been killed by the fire—they had been bludgeoned and stabbed to death before the home was set alight to destroy evidence of the grisly crime.

As the residence was transformed from a fire scene into a crime scene, investigators learned the home belonged to Savvas Savopoulos, the CEO of American Iron Works, a construction company specializing in building large commercial and government buildings. Investigators quickly identified the victims as Savopoulos, his wife Amy, their 10-year-old son Philip, and the family’s housekeeper, Vera Figueroa. Police reported that the child appeared to have been tortured prior to death in an apparent attempt to force his father to comply with the criminal’s demands. This compulsion appears to have succeeded because Mr. Savopoulos’ personal assistant reportedly delivered $40,000 in cash to the residence shortly before it was set alight. Mrs. Savopoulos’ Porsche 911 was found burning in a church parking lot in New Carrollton, MD later that afternoon.

The brutal murder of a family and their housekeeper in an affluent area of the nation’s capital garnered a great deal of media attention, and the case soon became known as the “mansion murders.” As the investigation into the murders began, it became clear that the Savopoulos family was taken hostage on the evening of May 13 and held overnight until Mr. Savopoulos could arrange for the cash to be delivered to the home. One piece of evidence supporting this theory was the fact that two pizzas were delivered to the home on the evening of May 14, which were paid for with an envelope of cash left on the porch. Those pizzas would ultimately help police identify the suspect through DNA recovered from a piece of uneaten pizza crust.

The DNA matched that of 34-year-old Daron Wint, a man who was raised in Guyana and moved to Lanham, MD in 2000, and who had a prior criminal history for theft, assault, sexual offenses, and burglary. Wint lived in an apartment complex close to where Mrs. Savopoulos’ Porsche was abandoned. In October of 2018, Wint was convicted on 20 counts of murder, kidnapping, extortion, and arson, and sentenced to four consecutive life sentences.

An Act of Workplace Violence

Even six years after the crime, there remain unanswered questions. What was Wint’s motive? Prosecutors were never able to provide clear proof of Wint’s motive during his trial, and Wint himself has refused to discuss the case even after his sentencing. However, from the facts we do know, it is clear this was not a random crime. According to police, Wint was employed as a welder with American Iron Works from 2003 to 2005, the company run by Mr. Savopoulos. He was reportedly fired after threatening a co-worker with a knife. After losing his job at American Iron Works, Wint had problems maintaining employment and contacted the company in 2008 and 2009 asking to be re-hired.

In 2010 he was arrested at a gas station across the street from the American Iron Works headquarters building. At the time of that arrest, Wint was reportedly armed with a BB pistol and a machete. The weapons charges were reportedly dropped when Wint pleaded guilty to charges of possessing an open container of alcohol. Based on the totality of these circumstances, it is clear that the home invasion and murders were clearly targeted, and an act of workplace violence.

That there was a period of 10 years between Wint’s firing from American Iron Works and the attack against Mr. Savopoulos and his family is somewhat unusual, but not unique in workplace violence cases involving “grievance collectors.” For example, Jarrod Ramos, the man who pleaded guilty to the armed assault against the Annapolis Gazette in June of 2018 that resulted in the deaths of 5 people, had sued the newspaper for defamation in 2012 (the lawsuit was dismissed in 2013).

Ramos appealed the decision, but an appellate court eventually upheld the dismissal in 2015. Ramos had made a series of threats against the newspaper via letters and on social media, but in 2016 he went silent. He broke his two-year silence with a vulgar Tweet shortly before his attack on the newspaper’s office.

In another case, Henry Bello conducted an armed assault against New York’s Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center in June of 2017 after being fired by the hospital in 2015 for sexually harassing a colleague. Nine days before the attack, Bello reportedly lost his job as a caseworker with New York’s HIV/AIDS Services Administration, which appears to be the event that triggered the violence. During his rampage, in which Bello killed one doctor and wounded 6 others, Bello was searching for a specific doctor, the one who forced him to resign amid the sexual harassment charges, whom he blamed for his misfortunes. That doctor was not working that day, and Bello’s attack ended when he killed himself.

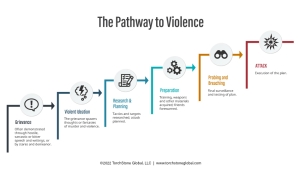

The bottom line is that Wint did not just accidentally show up at the residence of the CEO of his former company and kidnap, extort and murder the CEO and his family. This home invasion was the result of a decade-long process in which Wint had harbored and nurtured a grievance, thought about conducting an act of violence, and then planned and prepared for the attack. The process by which an aggrieved individual passes from holding a grievance to conducting an attack is known as the pathway to violence.

The Attack Cycle

One of the other still unanswered questions is how Wint planned the attack against the Savopoulos’ residence. A complex crime such as a home invasion kidnapping does not just happen. It is the result of a process we call the attack cycle.

Investigators obtained the results of searches Wint had conducted in his cell phone in the eight months prior to the murders, but there was no record that he had searched for the address of the Savopolous family or even for directions to the residence. This could have been a result of him conducting those searches using some other device; however, it could also indicate that he did not need to conduct the searches in the months leading up to the home invasion because he already had that information.

This is all pure conjecture, but it is important to remember that Wint was arrested in 2010 at a gas station across the street from American Iron Works. Such a location is a natural surveillance “perch,” or place from which to watch a target. As I noted in the piece I wrote on detecting hostile surveillance in February, places from which you can see a target’s residence or office are critical locations for those conducting surveillance and should be carefully watched by those wanting to detect surveillance.

It could be that Wint just coincidentally happened to be hanging out at a gas station across the street from American Iron Works in 2010 while armed—but I believe it is far more likely that he was in that location with the intention of conducting surveillance on Mr. Savopoulos or perhaps given the presence of weapons, even intending to attack him when he was arrested.

From Wint’s perspective, the American Iron Works building was a location known to be associated with Mr. Savopoulos, and it would have been a logical point to begin surveillance if he didn’t know his home address. It is entirely possible that Wint could have followed Mr. Savopoulos from American Iron Works to his residence—especially if Mr. Savopoulos was not practicing good situational awareness or looking for hostile surveillance.

Given the brutal nature of the murders, the fact that Wint was fired for threatening someone with a knife, and the 2010 arrest across the street from American Iron Works while armed, Mr. Wint appears to have harbored a grievance against Mr. Savopoulos for years. Some of Wint’s former co-workers from American Iron Works also noted in press interviews that they felt intimidated by Wint’s behavior before he was let go—a common occurrence in workplace violence attacks.

In most cases like this, the aggrieved individual signals his grievance through threats and other communications. Prosecutors searched for threatening communications as they sought to construct a motive for the attack and would have included such evidence as part of their case. However, no evidence of any threats or other direct contact or communication with Mr. Savopoulos was produced during Wint’s trial. I confirmed this with Megan Cloherty of WTOP News in Washington, who covered the trial closely.

Protective Intelligence Lessons

Despite this lack of clearly communicated threats, there are several things that a protective intelligence program could have done to prevent this attack.

Detecting Hostile Surveillance

It is important to recognize that communicated threats are not the only indicator of attack planning as a threat actor progresses through his attack cycle. As noted above, a complex crime such as a home invasion kidnapping requires extensive surveillance, and we can assert with some certainty that Wint must have conducted such surveillance prior to executing his attack. This surveillance would not only be required to identify the location of the Savopolous’ residence, but also to ascertain the pattern of activity at the household, the pattern of activity in the neighborhood, judge the security measures in place, identify security vulnerabilities, and then use these observations to plot how and when to enter the residence and assert control over the occupants.

Furthermore, would-be attackers are vulnerable to detection as they progress through their attack cycle—and especially so during the surveillance phase of their cycle. This is especially true for threat actors like Mr. Wint who have not received training in surveillance tradecraft. Such actors tend to be awkward as they conduct their surveillance and easy to identify—but only if someone is looking for them. As previously noted, I suspect Wint’s 2010 arrest at the gas station across from American Iron Works likely occurred as he was attempting to conduct surveillance, as he seemed sufficiently out of place that someone called the police on him.

One way to detect hostile surveillance is by deploying a protective intelligence countersurveillance team to watch for surveillance directed against company facilities, executives, and executives’ residences. They are highly efficient at picking out poor criminal surveillance.

A secondary advantage of employing countersurveillance operatives is that they are amorphous by nature, which makes them far more difficult for a potential assailant to detect than traditional security measures such as an executive protection detail. Even in cases involving a threat actor with very good surveillance tradecraft who is able to detect one of the countersurveillance operatives, the hostile actor’s anxiety will increase because he will have difficulty identifying the entire team. In many cases, this can cause him to make numerous false-positive sightings and hopefully redirect him to another, easier to surveil target—even if he is not yet noticed by the countersurveillance team.

A second way to increase the possibility of spotting hostile surveillance is to train corporate executives and staff in skills such as situational awareness and surveillance recognition. As noted above, criminal surveillance is generally poorly done and is not difficult to detect by an alert person.

Analytical and Investigative Support

Although countersurveillance teams are valuable, to be truly effective they must be part of a larger protective intelligence program that can provide the teams with analytical and investigative support.

Investigation and analysis are two closely related yet distinct protective intelligence components that can help to focus the countersurveillance operations on the most likely or most vulnerable targets, help analyze the observations of the countersurveillance team to search for patterns and anomalies, and investigate any suspicious individuals observed.

Countersurveillance operations must have the ability to record, database, and analyze observations over time and distance, and in different environments. Without this capability, it is difficult to note when the same person or vehicle has been encountered by different team members, on different shifts, at different sites, or over a span of time.

An investigative capability is also important. In most cases, something that appears unusual to a countersurveillance operative has a logical and benign explanation. Investigative teams can examine suspicious incidents or people in an effort to determine if they were innocent or sinister.

In addition to supporting the countersurveillance team, the analytical and investigative teams can also document, database, analyze, and assess threatening communications, and issue security alerts and notices. Protective intelligence teams can aid uniformed security officers or others responsible for monitoring building access by providing them with photographs and descriptions of people who have been assessed as posing a potential threat. The person identified as the potential target of the threat also can be briefed, and the information shared with their administrative assistants, family members, and household staff.

Training can be also provided to those threatened to help them practice good situational awareness, and they should be provided with contact numbers in case they spot anything suspicious.

Protective intelligence teams can also provide security support and advice to HR and people managers who are in the process of terminating an employee who might become agitated or violent.

Liaison

Speaking of hostile termination scenarios, it is sometimes necessary to request the assistance of the local police in a case where an employee becomes combative or makes threats. Such situations illustrate the importance of having a good liaison relationship with the appropriate law enforcement agencies.

Generally, liaison should be maintained with the law enforcement agencies that will be called on to investigate and prosecute illegal acts committed against your company and its executives, and this may involve several jurisdictions depending on where corporate facilities are located and executives live. I also recommend that protective intelligence teams establish close liaison with their counterparts at other companies in their area as well as in the same industry, because some threat actors can target multiple companies.

Organizations such as the Association of Threat Assessment Professionals (ATAP) the Analyst Roundtable and others provide protective intelligence practitioners the opportunity to meet, network, and share information.

Red Teaming

Another valuable role protective intelligence teams can serve is by acting as a “red team” that simulates the actions of a potential attacker to identify vulnerabilities in a security program. Most security measures are designed to look from the inside out, but a protective intelligence red team provides the opportunity to look from the outside in.

Red teams can be used to monitor the operations of executive protection teams, including analyzing the principal’s schedule and transportation routes to identify times and places where they are most vulnerable. Countersurveillance or even overt security assets can then be focused on the identified vulnerabilities. Since the most predictable areas to find and begin to stalk a potential target are at the home and office, special attention is provided to those locations.

Red teams can also help identify the perches that would most likely be used by a hostile actor surveilling a specific targeted site such as an office or residence. Once the perches around these locations are identified, activities at those sites can be monitored, either in a low-key manner or by overtly placing a security presence there, making it more difficult for assailants to conduct pre-operational surveillance without detection.

At the very least the perches can be identified to the executive protection team (or the principal if there is no protection team) so that particular attention can be paid to those perches for indications of surveillance.

Protective intelligence teams can also perform cyber red team activities, what we at TorchStone refer to as a Public Profile Assessment, or PPA. Criminals frequently do extensive Internet research on their potential targets, especially for more complex crimes like kidnapping, or a home invasion robbery. A PPA examines what information is available on the Internet that a potential hostile actor could use to begin to surveil a target. This information can then be used to design security measures or allocate security resources to address such vulnerabilities.

Duress Codes

Another protective intelligence tool that could have been useful in the Savopoulos case is a duress code, a seemingly innocuous word or phrase that is either inserted or withheld from a conversation to alert an outsider that there is a serious problem.

During the trial, evidence showed that Mr. Savopoulos either texted or made telephone calls to several people while being held hostage including his personal assistant, his company’s chief financial officer, and their other housekeeper, who was asked not to come to the house. Had the family and staff been trained to use a duress code, it is very likely that the police could have been alerted before the family was killed.

This combination of protective intelligence tools can be applied in an almost endless number of other creative and proactive ways to help keep potential threat actors off-balance and deny them the unhindered opportunity to conduct surveillance and plan an attack. Although a large global corporation or government might require a large protective intelligence team, these core functions can also be performed by a skilled compact team.

American Iron Works has less than 100 employees and like many companies that size, does not appear to have a corporate security program. For such firms, it is often more sensible to work with an outside firm to provide security and protective intelligence support.

TorchStone Global has assembled a team of world-class, highly experienced protective intelligence practitioners that includes investigators, analysts, and psychologists. We are in the Business of Before, which means using protective intelligence tools to proactively identify problems instead of waiting for them to appear and then reacting to them.

Our protective intelligence practice can serve as your organization’s protective intelligence team or come alongside to support and supplement the efforts of your existing team.

Much more detail on the Savopoulos case can be found in the WTOP podcast 22 Hours: An American Nightmare.