How to Practice Sustainable Situational Awareness

By TorchStone VP, Scott Stewart

I frequently write and talk about situational awareness, whether in relation to being gray while traveling abroad, exploiting vulnerabilities in the attack cycle, or the need for contingency planning. With all this emphasis on situational awareness, it seems appropriate to write a piece on how to practice it—and just as importantly—how to do so in a sustainable manner.

To start things off, I define situational awareness as simply paying attention to what is happening in the environment around you in an effort to identify and avoid potential threats and dangerous situations. Many hold the mistaken belief that situational awareness is only something that trained law enforcement and intelligence officers can do, but nothing could be farther from the truth.

Situational awareness is more a mindset than a highly refined skill, and anyone can practice it if they have the will and discipline to do so. Discipline and will are critical because complacency, denial, boredom, and distraction often prevent people from practicing the appropriate level of situational awareness for the environment they find themselves in.

Practicing situational awareness is the best way to spot developing threats and proactively act to either avoid them or mitigate their impact. Threats don’t just materialize out of nothing. There are almost always some sorts of warning signs that are missed due to negligence or a lack of awareness.

People planning an attack, consciously or unconsciously, follow a process when planning their actions. We call this process the attack cycle. This cycle will take longer for a complex attack such as a kidnapping or car bombing than it will for a simple attack such as a purse snatching.

Regardless of the complexity, the same steps will be followed; and the actors are vulnerable to detection as they progress through the attack cycle if someone knows how to recognize the signs and looks for them. Situational awareness is an important tool that allows people to proactively notice threats before they can fully develop, as it is always better to avoid an attack rather than to have to respond to one.

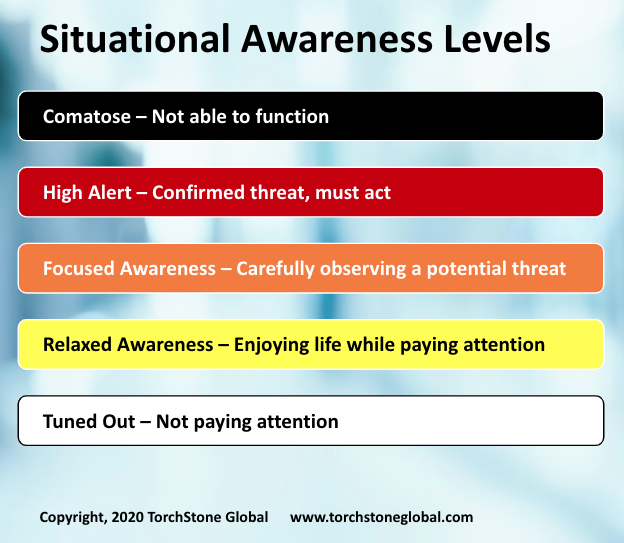

The Levels of Awareness

People typically operate in one of five distinct levels of awareness. There are various ways to describe these levels—Cooper’s colors is an example of a system frequently used in law enforcement and military training. However, I have found that civilians often have trouble relating to Cooper’s colors. Therefore, I’ve developed a five-tiered system based on the different degrees of attention people practice while driving to describe the levels of awareness, as driving is something that most people can readily relate to.

The five levels are: “tuned out,” “relaxed awareness,” “focused awareness,” “high alert,” and “comatose.”

Tuned Out

The first level, tuned out, is when someone is not paying attention to what is happening around them. It is similar to when someone is driving in a familiar environment, listening to a favorite song on the radio or daydreaming, and becomes even more dangerous when the driver is distracted by their cell phone or even texting while driving.

A person experiences tuned-out driving when they arrive somewhere without really thinking about their trip—or possible hazards along the route. We’ve all caught ourselves missing a turn because we were “on autopilot” and driving to a familiar place instead of the destination we actually needed to go to. This is tuned out.

Relaxed Awareness

The second level, relaxed awareness, is like defensive driving. This is a mental state in which one is relaxed but is also watching to see what other drivers are doing and looking ahead for potential hazards. For example, if you are approaching an intersection and another driver looks like he may not stop, tapping on the brakes to slow down is a good defensive move.

Defensive driving is not tiring, and one can drive defensively for a long time if they have the discipline to keep themselves from slipping into a tuned-out mode.

While practicing defensive driving, you can still enjoy the trip, look at the scenery and listen to the radio, but you cannot allow yourself to get so engrossed in those distractions that you ignore everything else. When you are in relaxed awareness, you can take time to smell the roses, but you make sure there is not a bee in the rose before you bring it up to your nose.

Focused Awareness

The next level of awareness, focused awareness, is similar to driving in hazardous road conditions. One must practice this level of awareness when driving on icy or slushy roads—or the pothole-infested roads populated by erratic drivers that exist in many developing countries.

When driving in such an environment, you must keep two hands on the wheel at all times and have your attention totally focused on the road and vehicles around you, never taking your eyes off the road or letting your attention wander. There is no time for cellphone calls or other distractions.

The level of concentration this type of driving requires makes it extremely tiring and stressful. A drive that would normally seem routine is exhausting under these conditions because it demands prolonged and total concentration.

High Alert

The fourth level of awareness is high alert. This level generally induces an adrenaline rush, a prayer, and a gasp for air all at the same time. This is what happens when a car runs a stop sign in front of you, a deer runs into the road, or a truck veers into your lane.

High alert can be scary, but one is still able to function at this level—you can hit your brakes and keep your car under control. In fact, the adrenaline rush you get at this stage can sometimes aid your reflexes. One struggle associated with this level is keeping the amygdala (sometimes referred to as your lizard brain) from taking over and reducing your ability to think rationally and diminishing your fine motor skills.

Comatose

The last level of awareness, comatose, is what happens when one literally freezes at the wheel and cannot respond to stimuli, either because you have fallen asleep or, at the opposite end of the spectrum, because you are in shock and unable to respond.

It is this panic-induced paralysis that is most important to consider in terms of situational awareness. In this state, the brain ceases to process information, and one simply cannot react to the unfolding situation. Many times when this happens, a person can go into denial, believing “this cannot be happening to me,” or the person can feel as though he or she is observing the event rather than actually participating in it.

Often, the passage of time will seem to go into slow motion or grind to a halt. Crime victims frequently report experiencing this sensation and often note they were frozen and unable to act as a crime unfolded.

Finding the Right Level—and Sustaining it

Now that I have defined the five levels of awareness, we can focus on identifying which levels are ideal for a given situation. The body and mind require rest to function properly, so sitting in your home in the tuned-out mode while watching a movie or reading a book is not only perfectly acceptable—but necessary. Unfortunately, however, some people practice a tuned-out mode of awareness in decidedly inappropriate environments—for example, using an ATM at night in a rough part of town, or walking to your car in a deserted parking garage.

If you are tuned out while driving and something unexpected happens—say, a child runs into the road or a car ahead stops quickly—you generally do not see the hazard in time, or you panic and cannot react in time to avoid hitting it. This reaction—or lack of reaction—occurs because it is difficult to quickly change mental states, especially when the adjustment requires moving several steps, e.g., from tuned-out to high alert. I liken it to trying to shift a car with a manual transmission directly from first gear into fifth, causing the vehicle to stall.

Indeed, many times when people are forced to make the mental jump from tuned out to high alert, they panic and their brains stall, going straight to the comatose level and unable to take any action. While training does help people become more adept at moving up and down the alertness continuum, it is difficult even for highly trained individuals to transition from the tuned-out to the high-alert level. This harsh reality is exactly why law enforcement and military personnel receive extensive situational awareness training.

I also want to pause here to note that situational awareness does not mean being paranoid or obsessively concerned about security. Indeed, I argue that hyperawareness is as destructive to personal security as complacency and denial. Humans were simply not designed to operate in a state of focused awareness for extended periods, and high alert can be maintained only for very brief periods before exhaustion sets in. As noted above, the body’s fight-or-flight response can be very helpful if it can be controlled.

However, when it gets out of control, a constant stream of adrenaline and stress is not healthy for the mind or body, and this serves to actually hamper awareness. Operating in a constant state of high alert is not sustainable, as all people, even highly skilled operators, require time to rest and recover.

When away from the safety and security of home, the basic level of situational awareness that should be practiced is relaxed awareness. This is a state of mind that can be maintained indefinitely without the stress and fatigue associated with focused awareness or high alert. Relaxed awareness is not tiring, and it allows you to enjoy life while also helping you protect yourself and your family.

When you are in a time and place where there is any sort of potential danger (which can be pretty much anywhere), you should go through most of the day in a state of relaxed awareness. If you spot a possible threat, you can “shift up” to a state of focused awareness and take a careful look at the potential threat while also looking for others in the area.

If the potential threat proves innocuous, you can shift back down into relaxed awareness and continue on your way. If, on the other hand, the potential threat becomes a probable threat, detecting it in advance allows you to take action to avoid it. In that case, elevating to a higher alert may become unnecessary because you avoided the problem at an earlier stage.

Once you are in a state of focused awareness, you are far better prepared to handle the jump to high alert if the threat does develop. Now, if you must venture into an extremely dangerous area, it is obviously prudent to practice focused awareness while there.

For example, if there is a specific section of highway where many kidnappings occur, or if there is a part of a city that is controlled and patrolled by criminal gangs, it is logical to practice this heightened level of awareness. This allows you to be prepared to ratchet up to a state of high alert in case you notice an indicator of a pending attack. However, once you safely get through that area, you can then shift back down to a state of relaxed awareness to recharge.

Sharpening Your Awareness

Practicing some simple awareness drills can help one become more adept at training the mind to switch between the different levels. When you are out on the street, take your awareness level up to a focused state for short periods of time. I often play a game by looking at the demeanor and dress of the people around me to try to figure out their “story”—what they do for a living, what they are doing at that moment, what type of mood they are in, and what they are preparing to do for the rest of the day.

“What if” drills are another useful exercise to help improve situational awareness. This is simply asking yourself, “What would I do if there was an incident in this location?” Then look at the place you are at and think through your options.

These drills are helpful both in places you are at every day, such as your home or office, as well as places that are new to you. You can ask yourself, “What would I do if an active shooter burst into this restaurant?”—and then identify exits you can use to avoid the attacker, things that can provide cover or concealment, places you could barricade yourself, and items you could use as weapons. I find these drills help train the mind to be better aware of such things and prepare you to be more aware of your options in case of an actual emergency.

Situational awareness is an invaluable security tool, and I hope this piece will help equip you to utilize it more effectively to protect yourself, your family, and your community.