The Disconnect Dilemma

By TorchStone TorchStone VP, Scott Stewart

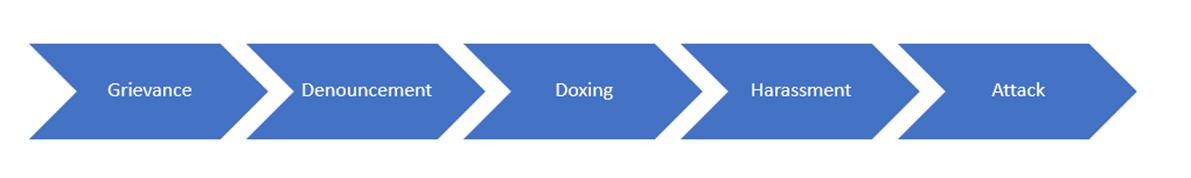

For the past few years, I have used the concept of the Social Media Threat Continuum as a model to explain the confluence of the leaderless resistance form of terrorism with the modern phenomenon of social media.

Briefly, the “social media threat continuum” describes the process by which “extremist influencers” use social media to air grievances to their followers, denounce enemies of their in-group, provide information about these enemies that can be used to target them, and then seek to influence their followers to harass or attack the identified enemies.

The grievances that begin the continuum are not threats themselves. The grievances span a wide array of extremist ideologies that include:

- Political grievances by the extreme left and extreme right.

- Religious grievances such as those embraced by jihadists and Hindu extremists.

- Single-issue grievances such as climate change, involuntary celibacy, or vaccine mandates.

These grievances can be either real or imagined. Just because a grievance appears delusional or fantastical to an outside observer doesn’t mean that it is not very real to the person holding it.

The extremist influencers promoting these grievance narratives will in most cases delineate the in-group impacted by the grievance, as well as the out-group blamed as being responsible for creating it. The extremist influencer may denounce the out-group generally by ethnicity, political party, religious affiliation, or industry; denounce them by name—or all of the above.

The Disconnect

Law enforcement in the West has been very aggressive and successful in holding extremist leaders accountable for the actions of their followers. Because of this, we have seen extremist influencers living in the West adopt the leaderless resistance model where they shy away from direct calls to violence and avoid direct communication with those involved in carrying out violent actions. Instead, they promote grievance narratives, denounce enemies, and provide targeting information while stopping short of a direct call to violence. This creates an intentional disconnect between the ideologue and the attacker.

This disconnect serves to provide plausible deniability and thus legal safety for the ideologue who has no tangible connection to the attack plot. It also provides security for the attacker since there is no group to infiltrate or communications with the ideologue to intercept.

Some groups outside the West such as the Islamic State are less concerned about legal jeopardy and are therefore more overt in their calls for attacks. They also tend to be more willing to communicate with would-be attackers.

This lack of disconnect has often proved detrimental to attack plots as infiltrators identify aspiring attackers to the authorities or communications that allow them to be identified are intercepted. Indeed, the recently thwarted Islamic State-linked plot to attack a Taylor Swift concert in Austria appears to have been detected due to such a connection when at least one of the would-be attackers uploaded a video proclaiming his allegiance to the terrorist group allowing him to be identified, and his attack cycle to be interrupted as he was attempting to manufacture explosives for the attack.

In recent years we have also seen numerous plots by so-called “siege culture” groups thwarted because they were attempting to operate as hierarchical groups, with connections between the leaders and would-be attackers. These cases and the thwarted Islamic State plots illustrate the risks associated with not maintaining a strict disconnect between ideologues and aspiring attackers fueled by the grievance narrative.

The Dilemma

The disconnect creates a dilemma for extremist influencers, however. While it provides increased safety for the extremist influencers and enhanced operational security for the aspiring attackers—and provides the influencers with a vast array of potential recruits who consume their propaganda—these benefits come at a significant cost.

First, the disconnect means that the extremist influencer does not have the ability to select operatives for an attack. Rather, the operatives are radicalized by the grievance narrative and then self-mobilized. Instead of being able to select the cream of the crop, they have the luck of the draw. While some grassroots operatives are intelligent and highly capable, others tend to be lacking in competence and ability.

Second, a strict disconnect makes it impossible for the extremist influencer to manage and direct the attack cycle of the grassroots operative. They have no control over the specific target chosen, the means of attack, or the timing of the attack. Self-selected operatives often merge their own specific grievances and motivations with extremist ideology, which can muddle the effectiveness of the attack. In Europe, we have seen a steady stream of low-level extremist attacks carried out by violent individuals with a criminal past, suggesting that they are either using the ideology as justification for their criminal activities or perhaps seeking martyrdom as a way to atone for past behavior.

Third, they are unable to equip the aspiring attacker with finances and training. Because of this, assailants operating under a strict implementation of the leaderless resistance model tend to possess far less terrorist tradecraft skills than professional terrorist cadres who can receive training from experienced terrorist cadres.

Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula attempted to rectify this problem by publishing instructional guides such as Inspire Magazine and even step-by-step bomb-making videos. They have also repeatedly urged grassroots attackers to conduct simple attacks with readily available weapons, rather than attempt attacks that were beyond their capability.

However, while we have seen a few attacks, such as the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing that followed this guidance and were directly linked to Inspire Magazine, there continue to be a large number of grassroots operatives (jihadists and others) who aspire to attacks that are beyond their capabilities.

These aspirational attackers are frequently ensnared in sting operations as they seek to acquire bombs or other weapons that they cannot create themselves. A prime non-jihadist example is the 2020 plot to kidnap Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer. The kidnapping cell’s lack of bomb-making tradecraft led them to invite a law enforcement officer posing as a bomb maker into their operational cell.

Finally, a strict disconnect complicates the ability of extremist influencers to exploit an attack. If they are unaware of an attack, it is more difficult for them to claim credit for it, and to also use the attack to draw new recruits to their cause. This is why the Islamic State likes aspiring attackers to provide videos of their pledge of allegiance to the group’s leader. However, as seen in the thwarted attack against the Taylor Swift concert, these pledges can leave a trail that provides authorities the opportunity to identify those planning attacks and take steps to interrupt their attack cycles.

This example illustrates the natural tension that exists between adhering to a strict disconnect for operational security—or maintaining some degree of contact with the attacker to either help facilitate the attack or benefit the exploitation of the attack by an extremist influencer.

How distinct extremist movements and even individual extremist influencers decide to address this dilemma may vary, but they will all be forced to reckon with it—as will security practitioners.

Additionally, security practitioners must be conscious of how their successes against an extremist ideology can force it to more strictly adhere to leaderless resistance and thus disconnect from aspiring attackers. Disconnected threats are generally less potent (due to the difficulties outlined above) but they are also more difficult to detect if the disconnect improves operational security.

This is the third part in an occasional series on the Social Media Threat Continuum. Part one discusses how the combination of leaderless resistance and social media is impacting the current threat environment, and part two examines the role of extremist influencers in this process.