Why is Protective Intelligence Effective?

By TorchStone VP, Scott Stewart

Quite often, when I speak or write about protective intelligence, I discuss why organizations should start a protective intelligence program, or I focus on a particular protective intelligence tool, such as baseline threat assessments.

Instead, I’d like to focus on why protective intelligence allows security teams to become proactive and prevent incidents rather than just respond to them.

Focus on Prevention

When it comes to security of any kind—especially protective security—it is always better to prevent an incident than to respond to one.

As studies by organizations such as the Force Science Institute have demonstrated, action is always faster than reaction.

This means that even a world-class security team will be placed at a disadvantage if an attacker is allowed free rein to plan and launch an attack.

In light of this reality, the emphasis must be placed on preventing attacks before they can be launched, rather than just responding to an attack.

This is not to in any way discount the importance of having a properly trained team to respond to an attack.

Clearly, attack recognition and rapidly responding to an unfolding attack are critical components of a comprehensive security program.

However, prevention should always be the goal of every security program, and the key to proactively preventing incidents is protective intelligence.

Attacks Don’t “Just Happen”

The critical factor that permits protective intelligence programs to prevent attacks proactively is that attacks don’t just appear magically out of the ether.

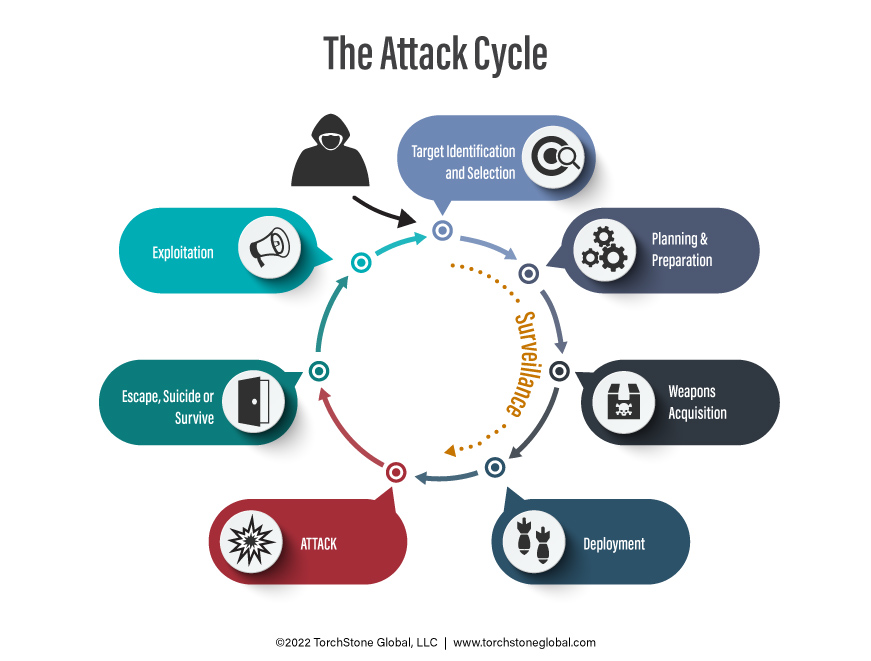

Attacks are the result of a process called the attack cycle, and the steps of a person advancing through the attack cycle can be studied, defined, and observed.

Observing behaviors associated with the attack cycle allow the attacker to be detected and the attack to be thwarted.

While it is possible to detect late attack cycle behaviors such as deployment at the attack site and avoiding an attack at the last minute, it is obviously better to detect pre-attack activity earlier in the cycle, and stake action to stop or avoid the attack when there is less imminent danger to the person or people being protected.

This is why protective intelligence programs should place emphasis on detecting surveillance in hopes of catching those conducting pre-operational surveillance during the target identification or planning stage of the attack cycle, well before the attacker is prepared to launch the attack.

The concept of the attack cycle pertains to all attackers: inside threats, external threats, known actors, and unknown assailants.

Anyone who wants to conduct an attack must progress through the attack cycle.

Now obviously, an assailant must put in much more time and effort to plan a complex attack, such as the kidnapping of a business executive, than for a simple attack such as an armed assault against a crowd of people at a lightly defended location.

But nevertheless, the attacker must follow the steps of the attack cycle.

He must identify a general target, select a specific target, acquire weapons, deploy, and attack.

I have an important secret to share with you: most attackers have very little surveillance tradecraft, if any.

Because of this, they tend to be really bad at conducting surveillance, and they are not difficult to detect if someone is watching for them.

However, they are able to get away with awkward surveillance mistakes and go on to launch an attack because most of their targets do not practice good situational awareness and are not watching for surveillance.

Sadly, this is not only true for the general public.

There are also security teams who are not focused on detecting pre-operational surveillance.

This was a major source of the failure with the executive protection team covering former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

They were inwardly focused and, unfortunately, did not catch the early stages of the assassin’s attack cycle, or even his deployment.

Videos of the attack show that Abe’s protection agents did not begin to react until after the first shot was fired, and that proved to be too late—action is always faster than reaction.

By focusing on pre-attack behaviors, and specifically pre-operational surveillance that occurs early in the attack cycle, protective intelligence operations can be very effective tools for proactively exploiting vulnerabilities in the attack cycle to thwart attacks.

People Don’t “Just Snap”

There is a popularly held misconception that people who conduct mass public attacks or targeted attacks “just snap” or “go postal.”

Studies of actual attacks demonstrate that attacks are rarely spontaneous.

Instead, attackers progress through a six-stage process developed by psychologists Fredrick Calhoun and Steve Weston called the “Pathway to Violence.”

Like the attack cycle, the pathway to violence is discernable, and because of this, it is a valuable tool for helping to prevent attacks.

Like the attack cycle, the pathway to violence is discernable, and because of this, it is a valuable tool for helping to prevent attacks.

As I’ve noted elsewhere, once a potential attacker progresses to stage three of the pathway to violence (research and planning), he has essentially begun the attack cycle at the target selection and identification point. In this way, the pathway to violence intersects with the attack cycle.

The pathway to violence model is useful because it offers analysts and investigators a way to understand the process that leads up to attack planning and execution.

But more importantly, using the lens of the pathway to violence provides a way to identify potential attackers before they begin their attack cycle.

In a corporate or organizational setting, educating employees about behaviors associated with the pathway to violence—specifically grievance holding and violent ideation—can help identify potential workplace violence threat actors before they act.

In a more general sense, educating people about the pathway to violence behaviors can help avert mass public attacks when people report such behavior to the authorities.

Countless examples of attacks have been thwarted when a concerned citizen alerted the authorities to a potential attack.

For example, on June 27, a San Antonio man with a history of mental illness was arrested after he told a co-worker that he was contemplating a mass workplace shooting at their workplace.

Such “leakage” is very common, and it is not unusual after an attack to see people come forward and report the gunman’s past threatening or troubling behavior.

According to a report published by the Texas House of Representatives on the May 24 school shooting in Uvalde, TX, the shooter was given the nickname “Yubo’s school shooter” by other users on the Yubo social media platform due to his fascination with school shootings and his repeated threats of violence and rape.

While the Uvalde shooter did not embrace a single coherent grievance narrative, his postings frequently exhibited violent ideation, some of them specifically about a school shooting.

The shooter in the May 14 supermarket shooting in Buffalo, NY, had been arrested a year before that attack and subjected to a mental health examination after he was reported to the police for making threats to attack his high school.

Yet, despite that incident, he was still able to purchase the rifle he used in the attack in Buffalo.

Additionally, the shooter embraced a clear white supremacist grievance narrative and had previously exhibited violent ideation.

It is exceedingly rare for there to be an attack in which the assailant does not exhibit some sort of personal or general grievance.

In cases involving unstable individuals, their grievances can sometimes be seemingly irrational or unreasonable, but they are nonetheless deeply held grievances.

It is also very rare to encounter a case of an attack in which others are not aware of the grievance and the attacker’s adoption of violent ideation.

While making threats or posting about violence alone is not always enough evidence to make an arrest, such indicators can at least bring a potential attacker to the attention of law enforcement.

In the case of the Uvalde shooting, a law enforcement visit to the shooter’s residence may have revealed the collection of firearms and ammunition that the shooter had legally purchased.

At the very least, reporting these behaviors can help paint a much clearer picture of an individual progressing along the pathway to violence and preparing for an attack.

Sometimes an interview by corporate security or law enforcement can be enough to help keep a potential actor from progressing along the pathway to violence.

Indicators that a person is progressing along the pathway to violence are almost always apparent to someone before an attack occurs, but if nobody is aware of what to look for, or who to report it to, the indicators are only reported after the attack—and that it is too late.

By identifying individuals who hold grievances and exhibit violent ideation, protective intelligence teams can help bring potentially dangerous individuals to the attention of security teams and, where appropriate, law enforcement.

Training employees on what to report, whom to report it to, and how to report it can help in gathering important pathway to violence information.

By assessing, investigating, and databasing potential threats, watching for potential surveillance, or signs that a potential threat actor is progressing along the pathway to violence, protective intelligence teams can play a critical role in thwarting attacks.

They are the tools that allow protective intelligence to be effective in helping companies stay “Left of Bang.”