Cyber Threats Part 3: Business Email Compromise

By TorchStone Senior Analyst, Ben West

Business email compromise schemes target businesses or individuals who transfer funds electronically.

Let’s examine the following hypothetical example:

It’s a Friday afternoon before a long weekend and only one employee in the accounting department is at work—his manager and co-workers have taken the day off to make the most of the weekend and there are no major projects due immediately.

At 4 pm the employee receives an email from what appears to be the CFO with an urgent message to call him immediately at a given number. The employee complies, calling the number and reaching the CFO who breathlessly thanks him for responding—he’s not been able to reach anyone else who can help him.

He carefully explains to the junior associate that there’s been a mistake—a major client has been overcharged and if it isn’t rectified immediately, the company is at risk of losing its most important client.

The CFO gives the junior associate instructions to transfer $2.5 million to a bank account immediately—they might miss their window if they don’t act before 5 pm.

Flustered, the junior associated completes the task and verbally confirms to the CFO that the transfer is complete. He goes home for the long weekend proud that he was able to help his company in a dire time of need.

Rather than being celebrated for his work when he returns Tuesday morning, his manager immediately calls him into his office demanding to know the meaning of the unauthorized $2.5 million transfer the Friday before.

The junior associate recounts the events of that afternoon and together, they call the CFO for clarification.

The CFO insists that he never requested such a transaction and that he had been traveling Friday afternoon to visit family for the holiday weekend.

There was no overcharge of the client and the account the junior associate transferred the money to was not associated with any of the company’s clients.

With the help of the IT department, the CFO and accounting department determine that the email sent at 4 pm the previous Friday came from an account that spoofed the CFO’s work email account by omitting a hyphen in the company’s name.

The email came from someone outside the company and the person the junior associate spoke to was not the CFO but a scammer. The legal department is involved and they encourage management to put the junior associate on administrative leave during the investigation.

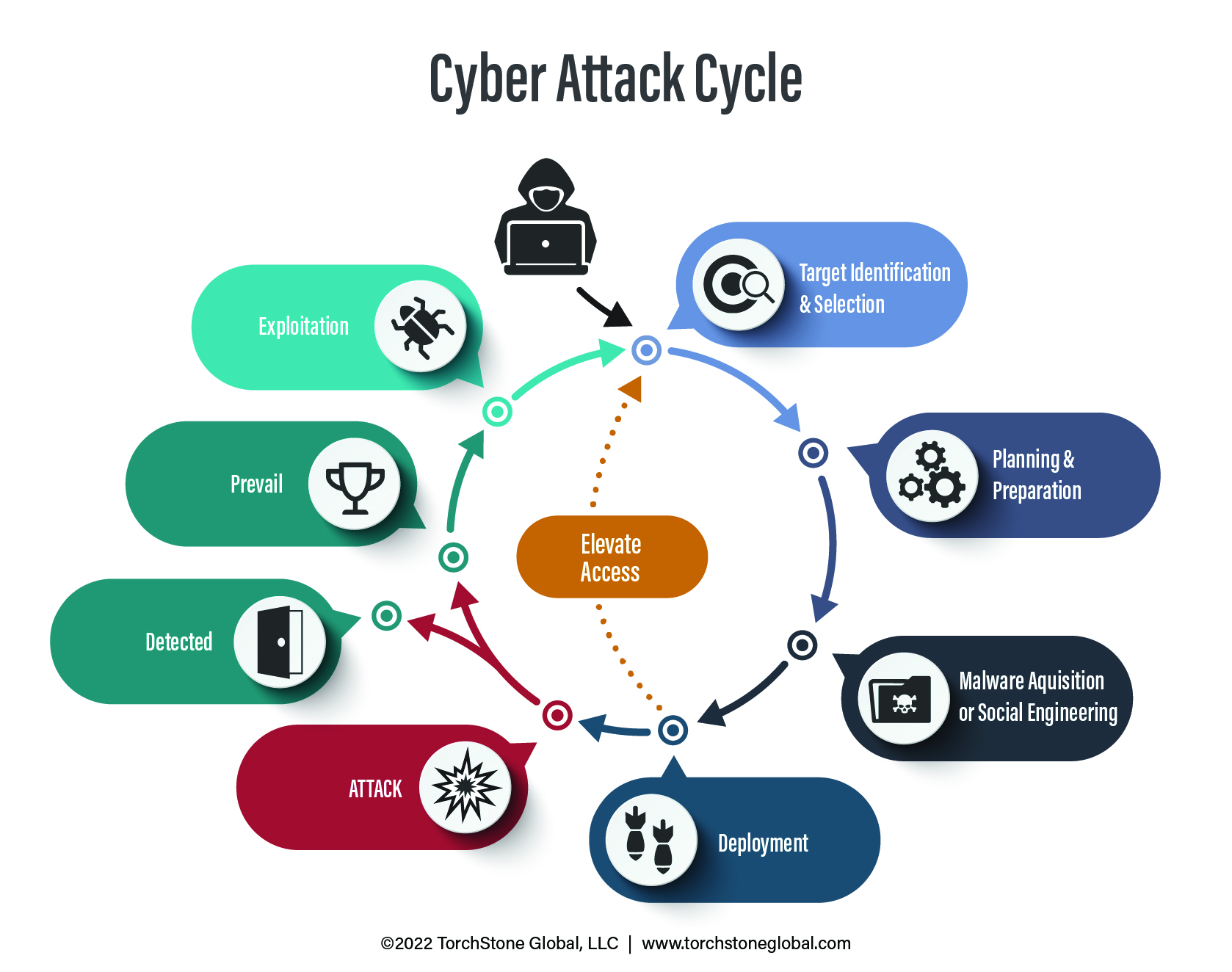

Cyber Attack Cycle In Progress

The scammer had been preparing his attack for months before executing it.

The attack originated from a spear phishing attack earlier in the year that managed to steal the Microsoft Office credentials from another junior associate who unknowingly allowed the attacker access to the company calendar and list of contacts.

The attacker tracked vacation schedules kept on the calendar and identified the Friday before the holiday weekend as the best time to strike due to low staffing and the absence of senior staff in the accounting department.

He was able to use open-source research to determine the name of the target company’s largest client and established a bank account in a name similar to the client’s company a month before carrying out the attack.

He established the spoof email address just days before the attack.

Establishing a foothold in an employee’s Microsoft Office account and collecting basic intelligence all helped the attacker elevate his access from a company calendar to $2.5 million.

After months of careful information gathering and preparation, the attacker exploited his access and information with a well-timed phone call and a bit of acting to complete the attack.

Gone Money Gone

By the time the victim company pieced this all together, the attacker had already transferred the funds out of the original bank account through a series of cryptocurrency platforms over the course of the holiday weekend and withdrew the money from a casino in the Philippines within a week of the original transfer.

The funds were lost.

The legal department was faced with the prospect of determining what to do with the junior associate.

There was no indication that he had acted against the company intentionally, but it was impossible to rule him out as a party to the conspiracy.

The fact that the scam was carried out over the phone meant there were no records of the fraudulent instructions so there was little law enforcement could do to help the victim company.

Thanks to the new Financial Fraud Kill Chain initiative, the FBI was able to freeze $328 million in fraudulent transfers, representing a 74% success rate.

However, retrieving fraudulent funds is difficult, time-consuming, and requires immediate action on the part of the victim.

In 2019, car-maker Toyota was targeted in a BEC scam that resulted in $37 million in losses through a process similar to the one outlined above.

In 2020, the Puerto Rican government lost $2.6 million in a BEC scam, and in 2021, Obinwanne Okeke, once considered a promising entrepreneur, was sentenced to 10 years in prison for scamming businesses out of $11 million.

The FBI estimates BEC costs businesses in the United States an average of $5 million per incident.

Clear Hierarchy

BEC doesn’t just cause financial losses through fraudulent transfers, it also causes losses in time and resources sorting out what happened.

It undermines trust in a company where employees can’t be sure who was fooled versus who was assisting the attack—even if the funds are recovered.

Companies can reduce the likelihood of becoming targets of BEC attacks by maintaining good cyber hygiene and establishing clear channels of communication.

First, cyber hygiene means keeping company devices, accounts, and networks clear of unauthorized intruders.

The more time and access an attacker has to a company’s digital assets, the more he can elevate access, increase the sophistication of the attack, and thereby increase the amount of money lost.

Denying attackers access in the first place by avoiding smaller-scale phishing attacks and reporting suspicious activity doesn’t guarantee that the company won’t be targeted by a BEC scam, but it denies the attacker the ability to collect intelligence that he can use to make his attack more believable.

Second, BEC scams prey on disrupted chains of command and urgency.

Companies should have clear policies in place requiring multiple forms of verification to complete transactions of certain amounts.

Behaviorally, executives and managers should respect chains of command and not make a habit of making extraordinary requests of junior employees—doing so only increases the believability of a BEC scammer.

This report is the third in a five-part series addressing cyber threats to organizations and individuals. The first part, Understanding the Cyber Attack Cycle, introduces the Cyber Attack Cycle and its progression. The second part, Phishing and Spear Phishing Attacks, demystifies the most common cyber security threat. The fourth part, Ransomware Attacks, discusses how information or network access may be held hostage. The fifth and final part of the series, Supply Chain Attacks, contends with the failure to secure a network.